inconsistently We got up before it was light and showered and dressed in the dark, then left silently, not wanting to wake up Rachel’s grandmother.

http://thmiii.com/case/14 The day was just beginning to lighten outside as we hit the road. Amazingly, the highway was already eight lanes of red lights plodding toward Denver. But we soon turned off the main road south and struck west, where we had open highway. We passed through Golden and thought of breweries, and then we were in the mountains. It is impressive how abruptly the mountains begin: they rose up out of the plains in a violent burst, which you can see even today. The highway runs up a dramatic “hogback,” as they are called, where the strata which had run flat across the plains for hundreds of miles suddenly rise and crumple and break, like a cake out of which emerges a dancer. We had seen nothing so violent all the way across the country, from New York City to Denver. Now we were seeing thirty-million-year-old violence, when the Rockies punched their way up out of the plains.

I have never completely understood why Denver became the capital of the Rocky Mountains, and I-70 offers no answers. The route was clearly built for Denver, not Denver for the route. Only a madman or a 20th-century American would have gone through the mountains this way; the highway in many places drops down to fifty miles an hour while it tries to squeeze through tiny canyons or go over 10,000-foot passes. Giant gates were visible in several locations where the road is closed for snow. The Rockies have several natural gaps, the most remarkable being the “Gangplank,” a bridge of land running straight from the plains near Cheyenne right onto the summit of the Continental Divide, the route of the Union Pacific, which sowed state capitols all along its chosen path; and a less spectacular but no less useful route, the southern one from El Paso almost straight across to Tucson where the Southern Pacific ran, which was so essential that the U.S. went and renegotiated its treaty with Mexico to get its hands on it (the Gadsden Purchase). Denver is not located on a natural gap and has no good route across the mountains. I believe Denver grew because of its mines, and by the time the mines were exhausted the city had grown enough to keep itself afloat. I-70 is a testament to American engineering but it is a strange road: crossing great mountain passes and passing through beautiful rocky canyons, it makes its way across remote Colorado and Utah, connecting not much of anything, until it ends at I-15 at a town called Fort Cove. But it offers another route for Americans to cross from east to west, which is our great passion, and the road gets a fair amount of traffic. It is beautiful too, though I wondered if a highway was the best use of these canyons and mountain passes.

I had the wheel first, as long time in the woods had made me the most reliable riser out of our group, and the one who did morning driving most effectively sans caffeine. None of us had breakfasted, and as we climbed higher and higher into the mountains we figured we would find a nice small town to have a good big breakfast. We went over Vail Pass – over 10,000 feet – and I figured maybe we’d stop in Vail. I had gotten postcards from Vail from classmates of mine at Princeton. If young Princetonians were hitting the slopes in Vail, there must be some legendary breakfast joint there, we figured. I had been to Telluride, another of the great ski resorts of the Rockies, and it was breathtakingly beautiful: maybe the most beautiful small town I’ve ever seen in America.

We were looking for something similar in Vail, and we were sorely disappointed. The place appeared to be a pre-fab piece of fakery, where you were supposed to stick your car in the big parking lot for $10 and then walk around “Vail Village,” which was about as much a “village” as a Holiday Inn lobby is the Bazaar of Istanbul. We had no interest in eating in a glorified hotel lobby-turned “village,” thank you very much. We shook the dust off our feet and kept heading west. We didn’t see a single real thing in Vail, though we were mighty impressed that the Vail police force drives Volvos – Volvo SUVs. You can’t make this stuff up.

We ended up breakfasting in Eagle, in the Eagle Diner, which satisfied all our expectations – we had a heavy mountain breakfast and stretched our legs most agreeably. By that time we were very nearly at the Colorado River, and already the landscape was beginning to change from Alpine to American West. The firs and spruces vanished and the dust and red rock began. I immediately began to miss the mountains: my eyes love the blue and green and gray and white palette of the mountains, but the tans and oranges and reds and pinks and blues and yellows and browns of the drylands are not for me: I never feel at rest in places where there is no water.

There wasn’t much to make us stop in such a landscape, so we headed straight for Utah. I wanted to visit at least one of the Utah national parks, and for whatever reason I had it in my head to see Capitol Reef. Arches was also on the way, but I wanted to see Capitol Reef. I think this was a mistake, born of a few nice pictures I had seen in my geology textbook in college, but I’ve got Arches in my future still.

We turned off the interstate and found ourselves on a straight local highway unadorned by a single building of any sort. We put on Paul Simon’s Graceland and I floored the pedal, singing along.

She looked me over and I guess

She thought I was all right –

All right in a sort of

A limited way for an off-night –She said don’t I know you

From the cinematographer’s party?

I said who am I

To blow against the wind.

I was driving over ninety miles an hour without noticing it. I also waved to every single car I passed, out of sheer joy of being alive, and not a single person showed any response, which we took as a further cause for mirth. The cars were obviously vacationers, doing the Utah National Parks, with plates from all over. There were a number of RVs.

We pulled into Capitol Reef. We passed a tiny redstone cabin where a man, his wife, and eight kids eked out their pioneer lives in the red rock. The rock was now familiar to me: it was the same rock, the same formations, you see all over northern Arizona and western Colorado, the rock of the Grand Canyon, Monument Valley, Mesa Verde, and innumerable Anasazi sites. Looking up at the yellows and pink rock-faces, some of them gorgeously smooth as if polished, I thought, “that’s Monument Valley.” Looking down at the gray and pink and white grit below I thought, “Painted Desert.”

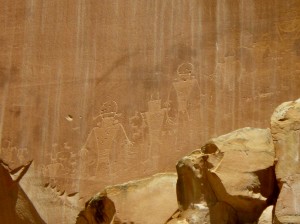

On one of the rock-faces were some notable pictographs, the finest I have ever seen, odd mythical figures which strike one immediately as the work of some ancient long-vanished mind, simple and yet entirely unlike anything we moderns would produce from our own inspiration.

We came to an old Mormon outpost, known by the name of Fruita, where the water is gathered by the valley and there are pioneer-orchards and cottonwoods shading a green lawn. Here we picnicked in the company of a sizable herd of nearly tame deer. The deer urinated so frequently in our sight it was hard not to believe that they were drinking just for the hell of it – because they were in Utah and there wasn’t a stream for a hundred miles in any direction and they knew they had it good. It was astonishing to see how green the river-bottom was against the stark rocks all around. On the rocks the vegetation so eschewed the color green it could not even be immediately detected by the Eastern eye.

We took the scenic drive, which was nice but it did not feel like anything but scenery, and we went on a brief hike into a slot canyon. It was a strange place: there is something about these places that makes me feel irresponsible – as if nothing quite mattered, perhaps because the land itself seems so unresponsive. I felt this in Arizona as well – what do concepts like “sustainable living” mean here anyway, where there is no sustainable source of water or food or fuel? You may as well just suck the tit dry now. No one will live here in fifty years anyway. I don’t enjoy this feeling, but I’m sure it’s a normal human response to the desert, and it explains a great deal of the culture of desert places in this era of massive importation of whatever people want to import. When all this is over, the deserts may return to the hardened Abrahamic monotheism of stones and serpents and manna and mercy.

Back at Fruita on our way out we admired some extraordinary old cottonwoods, which like the deer had grown almost ostentatiously fat on the desert springs, as if gloating in front of the other cottonwoods. Cottonwoods are fast-growing trees, and I did not imagine these were very old trees despite their massiveness: I think these things simply grow quickly when there is perennial sun, perennial water, and perennial warmth.

At the ranger station we got to look at the sun through a special telescope. Its sunspots were visible.

We then set off across Utah. As we got into its western reaches the elevation and precipitation increased, and I was surprised to see lovely pine forests clothing the mountain slopes. The towns were just a bit neater too, from the Mormon influence, and it looked to me like a place worth exploring more. It was certainly less barren than I might have thought from seeing the pictures of the National Parks.

We drove and drove and drove, and ended up that night in the southwest corner of the state, in St. George. We stayed at a well-run little motel right in the center of town, and we walked around to see what could be seen in the little downtown grid. The place had the feel of a resort town – it seemed to have no business but its climate. Groups of thirty-somethings walked by, all fit and all pushing baby strollers. We went to the old Mormon church – which was quite nice, and showed that in the 19th century Mormons like the rest of America did have a brief fling with aesthetic competence – and admired the perfectly pointed brick and manicured lawns and squared-off parking lots. The town had been the winter home of Brigham Young, and his house is still there, a fine New England Edwardian that could have been the home of any lawyer in any old Connecticut town. It’s odd to think of a Prophet of God living in such a place with a direct line to the Almighty from his butler-pantry or servants’-stair or fourth bedroom. But on the other hand it was almost the perfect synthesis of New England life, where the more bourgeois your life, the more direct your connection to God is believed to be. Of course there was a great deal more to Young, with his truly astonishing 55 wives, which again makes his conformity to almost everything else about 19th-century American life – from the starched shirts and beaver top hats to a paranoid fear of miscegenation – a kind of sick comedy.

We ended the night in the one bar in St. George. Utah prohibits the sale of alcohol except with meals, so we were obliged to buy food at this bar in order to be served a beer after a drive across the desert wastes – Phariseeism thriving wherever religion has power. However, the bar for this reason was all the more interesting a place – when there is only one bar in town, and where alcohol is considered a sin in itself, the outcasts have only one place to go, and all the more reason to cling desperately to each other. The place had sinners old and young, and it really did seem to me like it was the one place I would feel comfortable in town – with the acknowledged sinners, the divorcees, the outcasts, the people whose facades had long ago been peeled away by the harsh hand of personal failure and misery. Everywhere else in the country these people were normal, but in Utah they were unusual and had to huddle together. I saw immediately that an interesting book could be written about the bars and bar-culture of Utah. I had a “polygamy porter,” made by a Utah brewing company, which was not to my taste, but nevertheless I obeyed its sage injunction on the label, “why have just one.”

[Next installment here.]

One Trackback/Pingback

[…] night in St. George was our first in a bed – each night going across the country our hospitium had been a floor – […]

Post a Comment