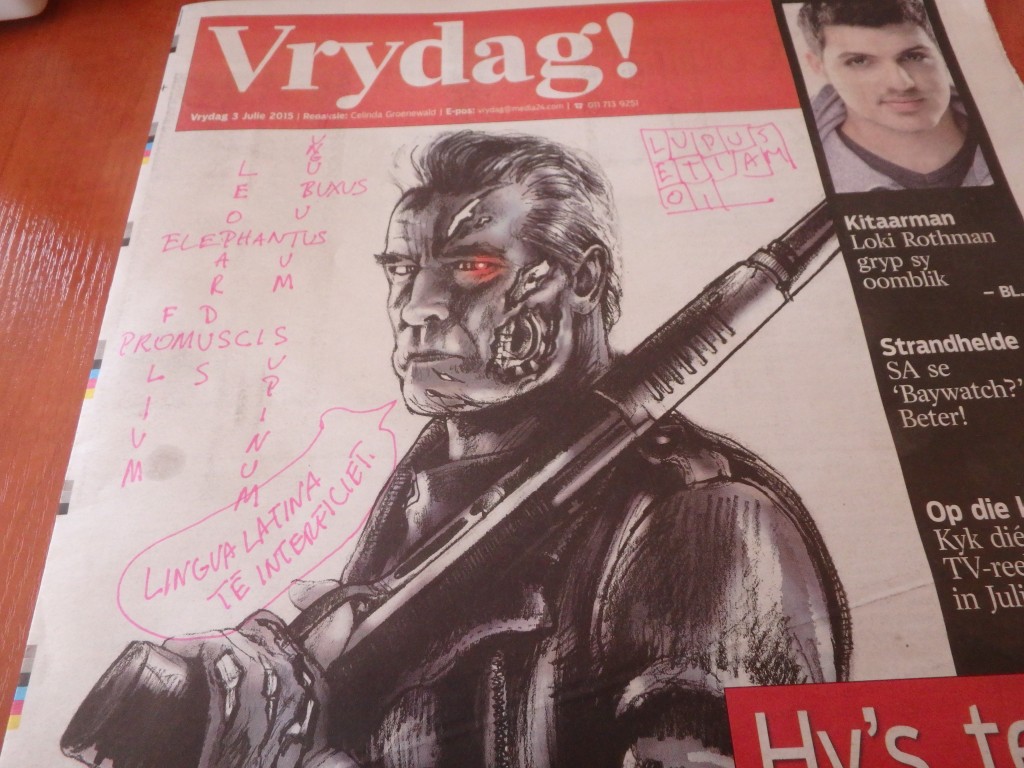

A most extraordinary thing today: the sort of thing which only happens when one is on the road. We were walking through the university campus, as I was hoping to catch a glimpse the university botanical garden before having to give a Latin tour of it later this week. As we walked we passed an older man, who looked like a retired college professor out for his afternoon constitutional; I made eye contact with him and said hello as we passed. Since the university is not in session, and almost the entire population here uses Afrikaans, my greeting, and, in general, our appearance, clearly stirred some curiosity in the old man, but politeness kept us moving in different directions. But chance made our paths cross again, about ten minutes later, after we had turned our course aside to look at some of the older, nicer university buildings (most of the buildings are modern and unattractive). It is an odd feature of our shared culture, that a single chance passing is not considered enough to allow a person to start a conversation: but two sightings will suffice. When we saw him again he smiled uneasily, looked a bit shamefaced, but summoned up the courage to ask, What exactly we were doing here? We explained that we were Americans teaching an immersion class here; he asked in what, and we said Latin; and he reacted with evident joy, that something so old and forgotten, but so precious and dear should still have some life in it; the way an older woman in town might react to someone harvesting apples from a long-neglected orchard, and making apple butter from the trees again, the way she used to when she was young. “Are they still doing that? I’m so happy!”

He was so pleased with it, and was so genteel and lovely, that he invited us to his house for tea, which he said was not far away; in fact it was on the university campus. I wanted to get to the botanical garden, but when on the road you are closer to the truth that every open door is soon closed forever. I felt proud to be with Nancy Llewellyn, my colleague, who made the decision for all of us, not consulting us any further than a glance, and made it as she always does, correctly. “We’d be honored,” she said. Off we went to this man’s house, a short walk away.

We were walking with Hennie Coetzee, a former professor of music, now retired. He brought us to his property, a nice corner plot where he apologized for the untidiness of the very tidy garden, noting that “we do all the gardening ourselves.” He led us to a small outbuilding next to his house, his study, and went off to inform his wife that he had brought guests for tea. The study was chock-full of interesting objects: the walls lined with bookcases of of superb books, a baby grand piano, his CD collection, much sheet music, all kinds of knick-knacks, images, busts, paintings, mostly of the great German composers, Mozart, Wagner, Beethoven, Schubert, Bach; but all sorts of things were there, a bust of Byron, watercolors of churches, old souvenirs of Venice and London and Rome (a fine brass Lupa Capitolina, no less). He came back and asked if we would like to hear him play the piece we had been discussing just earlier, an impromptu by Schubert (we had asked him what music he most loved and most often returned to). Of course we were thrilled, and he played through the whole piece, flawlessly and with great feeling. He seemed to be pleased to have appreciative ears for the skill of his hands. Having learned of my interest in botany, he then showed us a splendid monograph of botanical art on the genus Mimetes, of the Proteaceae, published, at what must have been great cost, a few decades ago by Kirstenbosch; we learned from it the Latin adjective hottentoticus, as in Mimetes hottentoticus.

Looking over John Patrick Rourke's Mimetes monograph, illustrated by Thalia Lincoln.

We then entered his house, and if we thought his study was a study in culture and ornament, his house must have been an encyclopedia: room after room completely filled with antiques, of every sort: many personal (pictures of long-deceased family members, his wife’s parents’ wedding announcement, old uniforms and weapons and other accoutrements); many South African (images of Boer presidents, memorabilia from the Boer War, images of South African homes and churches, old maps, etc.); many pertaining to European culture generally (a superb collection of Delft ware, images of Napoleon, coronation teapots from British monarchs, etc.); and the objects were of every description, fine old furniture, old advertisements, coins, prints, lamps, glassware, letters and other documents, bric-a-brac of every sort. Every room was chock-full of things. My mother’s house always astonishes people for its density of object and ornament, and my nieces and nephews think of it as like a museum: but this was the most densely decorated, thoroughly curated collection of antiques I had ever seen in one place. It was like an antique shop, but it was most emphatically a home: there was not a speck of dust anywhere, and the objects were all clearly curated, which is to say they were all united by a human personality, and were not just a collection of random things. I stopped at an oil portrait of Goethe, a copy of a famous one made later in his life, and — said, “We believe that painting belonged to Adolf Hitler.” I let him talk: “I bought it at an auction where were many of the personal effects of a high-ranking German official, who after the war got possession of many of Hitler’s things. We think this was one of them.” It was bitter to me that Hitler could so stain Goethe by owning so much as an image of him; bu if we needed an image of the moral uncertainty of the project of high-culture represented by Goethe (and the very house we were in), here it was.

We met his wife, a retired theology professor herself, who brought us into the kitchen and plied us with fine tea and mountains of cookies, and she acted offended at the thought that we would have only one cookie each. She apologized profusely for her state of dishabille, a word which to her nevertheless meant having more perfect clothes, hair, and makeup than the rest of us put together. They told us of their trip to America, which included a trip to Traverse City, Michigan, because their son was studying at the Interlochen Music Camp, and New York City. They professed an admiration for America, which seemed quite genuine. And she too was charmed to admiration, hearing that we were Latinists. She pointed out a cross in the kitchen, on which was inscribed “Vita Sine Amore Mors Est,” which she said was made by an Italian prisoner of war during World War II; apparently Britain sent many of its war-captives to work on farms in South Africa during the war. There were several such objects in the house, and in retrospect I realize that there is likely a more personal story here: they probably personally met some of these captives. She said they were wonderful people, talented as both farmers and craftsmen.

We had to go, as we had a dinner appointment, but we knew that we had met one of the most interesting families and been in one of the most interesting homes in South Africa; in fact, when we mentioned it this evening at dinner with some other professors, they said they had heard of this extraordinary home, and hoped to see it someday.