A very nice piece from the National Catholic Reporter, in which a priest simply records all the reasons he is given for young people’s dissatisfaction with the Church, in an evening devoted to the topic. Every single reason is a good one. Almost every single problem the Church has in bringing the Good News does not come from Jesus: built on sand, it will wash away. You can see the problems in the comments section too. It literally devolves into fights about whether women monitoring the viscosity of their vaginal mucus counts as a Christian mode of birth control or not. Almost everything you hear from the pulpit or from the sacristy rats can be summed up as “Strain at gnats, and swallow those camels.”

Why Young People Don’t Go To Church.

18-Jan-15Against The Queen of Pentacles.

17-Jan-15

Suzanne Vega put an album out in 2014, “Tales from the Realm of the Queen of Pentacles,” which is at least one (and probably two) too many prepositional phrases, but the concept of the album is intriguing: Pentacles, she explains, in the Tarot deck are the suit of the material world; of comforts, the earth and generosity, but also greed and selfishness; our age, in general, and New York, her city (and mine), in particular. I love how she captures the hatred of the anti-materialistic man – and what is he but a Fool? – and then dissolves it again into a devil-may-care attitude.

How I hate the Queen of Pentacles!

Sitting on her golden throne

In her domestic tyranny

All roads lead back to her alone.The whole wide world is a great big drain

And the vortex is her heart.

Her needs and wants and

Wishes and whims

All take precedence on this chart.But what do I know?

My card’s the fool, the fool, the fool

That merry rootless man,

With air beneath my footstep

And providence as my plan.

Providence as my plan.Oh it’s such expensive innocence!

Never knowing any cost.

She throws around her finery

For us to fetch when it gets lost.But what do I know?

My card’s the Fool! The fool, the fool.

That merry rootless man.

With air beneath my footstep

And providence as my plan.

Providence as my plan.

The Pope has weighed in on the Charlie Hebdo killings, and he falls into the “Well, I don’t like murder normally, but…” camp:

The Holy Father spoke to journalists in a broad interview on the papal flight to the Philippines about the Charlie Hebdo massacre and the controversy about the magazine’s new cover this week. Religious freedom and freedom of expression, he said, are fundamental human rights. But they are also not a total liberties [sic]. “There is a limit,” he said, speaking in Italian. “Every religion has its dignity. I cannot mock a religion that respects human life and the human person.” He broke it down in everyday terms, something that is coming to be known as classic Francis teaching style. “If [a close friend] says a swear word against my mother, he’s going to get a punch in the nose,” he explained.

Or if a close friend says a swear word against my mother, I’ll kill him, and his friends, and also anyone who tries to stop me, and then head to a Jewish bakery and start killing people there too, because hey, it was my mom.

The Gospel message of course is quite different. In the Gospels, Jesus offers nine beatitudes, showing nine Christian spiritual practices, and interestingly, one of them is specifically being insulted:

He said: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.

Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are you when people insult you, persecute you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me. Rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

Every single one of these beatitudes, treated as a spiritual practice, yields interesting results, and creates a spiritual life quite different from those recommended by other traditions. I have much to say about all of them, but here I will focus on the ninth, often (but unnecessarily) treated as a subset of the eighth.

I have always been curious about the spiritual guru Gurdjieff, who made insults one of his primary modes of training his disciples. The theory behind it is that a human being who can be easily affected by the words of others necessarily is not conceiving of themselves in sufficiently broad perspective. We attach ourselves to small things: what we look like in the mirror, how much trivia we have stored in our brain, what clubs we are part of – and the result is a kind of narcissistic paranoia, always poised over the abyss, always hanging by a thread, always craving more validation from some new source. Maturity must involve some kind of severing of this addictive umbilicus, and one of the ways of doing this is precisely what Jesus praises as a way to blessedness: suffering opposition, and particularly insult and false testimony. There is an entire tradition of Christian spiritual practice trying to be a “holy fool,” a person who seeks to be good but does not want any worldly reward for it. To have a good reputation is to ask in a temptation, which is to be good for the sake of one’s ego. When you come to the realization that almost all of your good deeds are just a form of narcissism, and you are really no better off spiritually for all your “good deeds,” – that is one of the realizations that can produce actual transformation, into an entirely different kind of goodness. One that ends up being a lot less impressive to other people – the flash is gone – but a lot more honest, and a lot less wrought.

This spiritual practice of leads naturally to a respect for freedom of speech, and of course, freedom to insult and blaspheme and everything else. The Verba Seniorum speak of a “wise man” who sat at the gates of Athens, insulting everybody – this was thought of as wisdom:

Once there was a disciple of a Greek philosopher who was commanded by his Master for three years to give money to everyone who insulted him. When this period of trial was over, the Master said to him: Now you can go to Athens and learn wisdom. When the disciple was entering Athens he met a certain wise man who sat at the gate insulting everybody who came and went. He also insulted the disciple who immediately burst out laughing. Why do you laugh when I insult you? said the wise man. Because, said the disciple, for three years I have been paying for this kind of thing and now you give it to me for nothing. Enter the city, said the wise man, it is all yours. Abbot John (the Dwarf) used to tell the above story, saying: This is the door of God by which our fathers (and mothers) rejoicing in many tribulations enter into the City of Heaven.

If there were no freedom of speech, there would be no wise men sitting at the city-gates insulting people either. At some point, someone’s “dignity” would get ruffled, and they’d get rid of the wise man. And that is the enemy of free speech – that word used by the pope – a sense of “dignity,” that social stiffness brought on by social climbing, which makes it so humiliating for us to be exposed as no better than anyone else. It really is the enemy of the spiritual life as well. There is a fine story of St. Philippo Neri, who was sent to investigate the claims of the saintliness of a particular nun. He rode all day through the rain, and meeting her in the reception-room of the convent and seeing her gleaming, potentially vainglorious garments, his sense of suspicion was aroused. He told her his feet were hurting but he couldn’t get his muddy boots off; could she help him? She took offense at even the suggestion that she should take off some stranger’s muddy boots, and so he stood up and left. Whatever she represented, he was convinced it wasn’t Christianity.

Jesus does not, of course, say that giving insult is one of the ways to blessedness; it may be necessary for a Christian to be insulted, but to choose to be the person who insults others necessarily has spiritual dangers. Gurdjieff may not have ended up being a very nice person. But Christians who understand their own tradition should have no problems with mockery and abuse. Jesus puts undergoing mockery and insult up there with seeking justice, or seeking peace.

Let me also note one thing about blasphemy. There are blasphemy laws in countries like Ireland (now looking at getting rid of its statute) and Italy. These laws, all over the world, should go. Christians should certainly oppose them – Christ himself was brought to trial under such laws. The very notion of “offering insult to the Deity” is comical – I am quite certain the Deity can handle it. Muslims often think that the Christian idea that God can have a son is inherently blasphemous; whereas I, a Christian, think that having a son is not degrading at all, and many things religions ascribe to God are far more degrading than children would be. But all of it is projection. To make laws based on such projections is self-evidently unwise. Blasphemy laws are typically considered just “breach of peace” laws, but sometimes the peace gets disturbed. They say there was a riot when “The Rite of Spring” was performed. This is not a reason for prosecuting Stravinsky.

This is not to say that there are not things that are holy – there are – and that how we treat these holy things doesn’t say a tremendous amount about who we are. But that self-unfolding is holy too. As we do it, of course, we rely on others to mirror it back to us, sometimes mockingly, and in that process we learn to see.

Wild, The Movie.

10-Jan-15When you are in nature for extended periods, especially when alone, the membrane between yourself and the outside world gets thinner. The vocabulary of the forest and the wild starts to suggest itself in your dreams, and the sensory force of it begins to unlock your memories. The more extended the trip, the more thoroughly intimate it becomes; to go out, you find, is really to go in.

I think it was the dramatic presentation of this fact which made me love the movie Wild so much. The movie immediately calls to mind the movie Into the Wild, which is thematically similar, but this movie is effective at very different things. Into the Wild made American life on the road, in the form of its characters, seem appealing, and made me want to go out there and see it for myself, but when it got to real wilderness all it could offer were some postcard images overlaid with Eddie Vedder spirit-music, as if embarrassed, afraid that the image itself, and the silence itself, could hardly attract a modern person.

Wild is quite the opposite: it makes most human beings seem troubled, or annoying, or superficial, or dangerous, or boring; necessary sometimes for companionship, but hard to be around for long and certainly worth escaping. But that inner journey into aloneness – there, something worth having can be found. It is not misanthropic: it simply suggests that if you go off on a long hike, to the “Bridge of the Gods” (a real place, and the actual destination of the hike, which is wonderful) with an acknowledgement in your heart that you simply cannot solve your own problems and you need help – that if you go on a pilgrimage, in short – and give it enough time, you will find something.

The transformation comes about in part through encounters with people, but the movie is honest about the fact that for the most part people are just good companions for a little while, and not gurus placed by Providence at key points to offer the next piece of the Enlightenment Puzzle. For the most part the method in the movie is memory.

Memory fascinates me in many ways. It is so wildly selective – out of all the impressions that flit past one’s senses in a lifetime, only a tiny percentage leave any enduring trace. But the psyche often has its own reasons. The vocabulary of our memories is restricted to certain people or certain feelings the way the vocabulary of our dreams is restricted. But this may have a rationale, and a long period of time for reflection may help release the lessons implicit in our memories.

Dostoevsky says in The Brothers Karamazov, “You must know that there is nothing higher, or stronger, or sounder, or more useful afterwards in life, than some good memory, especially a memory from childhood, from the parental home. You hear a lot said about your education, yet some such beautiful, sacred memory, preserved from childhood, is perhaps the best education. If a man stores up many such memories to take into life, then he is saved for his whole life. And even if only one good memory remains with us in our hearts, that alone may serve some day for our salvation.” Preeminent among all good memories are the memories of joy: real, wholehearted joy, standing utterly beyond both happiness and pleasure, either our own joy or someone else’s.

In the case of Cheryl Strayed, the author whose memoir Wild is a depiction of, those joyous memories were of her mother’s joy, who is radiantly played by Laura Dern. Dern’s acting beautifully renders a woman who fits the basic facts Strayed offers: a mother who had married a physically abusive man, but defended herself by leaving him and ultimately did not regret marrying him because of her abounding love for the two children of the union; who raised her children always near poverty, waiting tables, but who was aglow with her desire for their betterment; and had some simple, unsophisticated pleasures which brought her real joy – dancing in the kitchen to certain popular songs, or pop books (Strayed brought along one of her mom’s potboilers on the hike, even though she had always looked down at them as books before). The screen images of Dern dancing or smiling or laughing are unabashedly beautiful, and utterly sufficient for someone’s salvation.

And the contrast between them and Strayed’s own life feels like a kind of engine pushing her forward. Strayed, after her mother’s early death (she lived only to age 45), found herself utterly joyless: she married a man who is portrayed as good, but she cheated on him again and again and again; leaving him she hooked up with a heroin addict, started taking heroin herself, got pregnant, had an abortion, finalized the divorce, and admitted that her life was out of control and she had to get out of it somehow. Drawn by images she had seen of the Pacific Crest Trail, she decided one spring to go walk the whole 1,500 mile route.

I think this represents a good human instinct. It is an old one: Chaucer talks about how in spring

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seeken straunge strondes.

When our life gets too difficult and painful to endure, I think one of the very good answers is to leave, and to leave naturally, i.e. best on foot, and bike is maybe acceptable as well. Pilgrimages are very old, and the custom probably comes from precisely this problem in our human natures: somehow we can go astray, and only a return to simplicity can restore us to the path. The focus in the pilgrimage tradition as it exists today is typically on the place, the destination, but this is, I think, a short-circuit in the system which the tradition itself could not have foreseen. I think we all understand intuitively that grabbing the next flight to Compostela is not the way to break through to a higher level of awareness.

What is the way, then? I think we get the answer from another great line of John Muir’s (he is, of course, the patron saint of the Pacific Crest Trail): “Few souls are inhabited by so satisfied a soul that they are allowed exemption from extraordinary exertion through a whole life.” And an extraordinarily unsatisfied soul is condemned, by a law of nature none of us can deny, to incredible exertions.

And so we see Cheryl, again, by an instinct which is notable, underpreparing herself for her trip, overpacking in a way which is in part naivete but also certainly part subconscious self-flagellation. She carries a burden which represents the absolute maximum of her physical abilities, and she does not discard the items until she has completed the first section of the journey, and, figuratively, the burden begins to be lifted. (There is an even more beautiful cinematic portrayal of this in the film The Mission. The DeNiro character, after killing his brother, is employed by a Jesuit to help build a mission. On his way up to the site, he must carry something like two hundred pounds of weapons and armor for days through the jungle, suffering terribly as he tries to move forward. Watching him struggle up a mountainside, one of the Jesuit novices goes to him out of pity and cuts the pack off his back with his knife; the pack goes crashing down the mountainside, hundreds of feet below, and DeNiro, without saying anything, but again, with the look of the greatest suffering, simply limps down the mountain in his bare feet after it, to bring it back up again. There was no setting him free from this terrible burden until it had been worked off, truly and fully and spiritually.)

Wild depicts these kind of exertions over two hours, and the suffering involved is both physical and mental. The result is that the movie is hardly easy watching, and I’m sure for people who just want a little two-hour escape the movie will not please. But I was happy with it, because it represented, cinematically, something which I think really does work for people, as therapy: work, and animal work, i.e. the work of survival. Get out there, and make it to the end a thousand miles later: carry your own pack, feel the hollow of your back sweat against it; learn to long for just a drop of water; learn what you really need and what you can do without; learn to be amazed that human beings can make something so amazing as a Snapple; go need someone else’s help; go put yourself in danger and do something smart to get yourself out of it; go fall into a stream and dry your clothes in the sun; go lay in your tent and ache – ache – for a person to talk to; get a fever and dream about your blankets as a straitjacket of ice or fire; hear the coyotes, see the stars, learn to eat cold mush with relish because of your hunger; throw your pack down at the top of a pass and feel the cold wind start to pick the sweat right off your body; get everything you own soaked in the rain and wonder how you could ever have been unhappy in a place that had a warm, dry bed. All this strikes me as good and healthy and restorative, because I think there is a cosmology implied in all our encounters with our own weakness and the Wild’s vastness, and this returns us to perspective.

I was impressed by how much of this experience the movie captures; and it captures more too. The vulnerability of traveling alone as a woman; the gratitude for people’s kindness; and many of the cameo portraits of people met on the trail are quite lovely in their own right, though never so precious as to be unrealistic. And the narrative structure of the movie is to tell Cheryl’s past in a series of memories, many of them quite convincingly and impressionistically tied together as bundles of similar images. They come in three categories, generally speaking: childhood trauma; adult bad habits; and those radiant childhood memories I spoke of earlier, which in the end help guide Cheryl to “being the woman my mom taught me to be.” They are all convincingly done.

I have read a few other reviews of Wild, and they seem to come in two categories themselves: those which praise it and those which think it’s Hallmark boilerplate and Oscar-bait. I really don’t think any movie with conclusions like “I learned something from heroin,” is Hallmark boilerplate, and if Oscar-bait means narratives with ambition, then of course you can expect me to like Oscar-bait movies. Reese Witherspoon is of course a bit pretty to play almost anything but a Hollywood actress, but since female beauty typically gets along nicely with self-destructive behavior and the kind of desperate sexuality Cheryl was trying to get away from, Witherspoon’s casting is always within a stone’s throw of the plausible, and once you get past the silly scene where she can’t move her pack, the acting afterwards is cinematically convincing. And indeed as a narrative the movie is most unusual: I think so deep a portrait of a middle-class woman (a waitress), one who is not especially competent or funny and not anybody’s mom or wife or anything else, but just a woman alone and out on her own, messed up and trying to get better, is actually quite rare in cinema. I’m glad we have it.

The Silent Majority Against Justice.

09-Jan-15The term “right wing” comes from the Estates-General of France: the king would sit in the middle of parliament, with the nobles and bishops on his right, while the representatives of the people would sit on the king’s left. As a Christian I still scratch my head about this: “What were the bishops doing over on that side?” All you have to do is look at the Gospel and the early epistles to see how little patience the Christian movement had for rich people: “the poor He hath filled with good things, while the rich He hath sent empty away;” “now weep and wail, you rich people, for the woes that are coming to you.” How in the world did we get from thirteen poor guys in a boat – with a noticeable animus against rich people – to a world where the “Christians” fight with the rich against the poor?

My mother, like many others of her generation, reads The Tablet, “The Catholic Perspective on News and Opinion from Brooklyn and Queens.” As she has gotten older and wiser, she likes it less, but she still reads a few of the columns by the priests, the ones which are more or less sermons on the topic of how to be good in one’s daily interactions with other people. I generally don’t read it at all, but the Dec.27-Jan.3 issue ended up in my pile of firestarter material in my cabin, and I started reading it. And what did I find in it but an editorial about the murder of two police officers in Brooklyn.

Before I get to the text of the editorial, let me make it clear: this newspaper is, according to its own proclamation, “Published by and in the interest of The Diocese of Brooklyn.” Its publisher is the bishop of the diocese of Brooklyn, Nicholas DiMarzio. And this is an editorial, by the editor, and not outside or even columnist commentary which may or may not represent the opinions of the bishop of Brooklyn.

The editorial is online, but I will also provide it here:

The year 2014 has not been the best of years. And unfortunately, it is ending on a sour note with the assassination of two police officers right here in our diocese.

The charlatan politicians and would-be community leaders would have us believe that the underlying problem is racism. The real danger facing us is the extreme lack of respect for authority which makes up the underpinnings of society.

The rabble-rousers leading the misguided public demonstrations in our streets would have us believe their cause is just. That is a smokescreen for arousing chaos and taking down the tenets of modern society.

The real issues of injustice begin in the homes and in families. The breakdown of family values and structures has led to a devaluation of human life. The real questions facing us center around why there are so many fatherless or motherless households in our nation. Why is there so much violence and disorientation among our young people? Why are there not enough jobs for all people? Why is our educational system failing to properly form young people? Why is there such callous disregard for unborn life?

Race is a factor but it is not THE factor. Our country has faced up to its racial divide and has been making great strides in bringing all peoples together. For the most part, people of good will live and work side by side, regardless of race, color, or beliefs.

But there are phoney leaders who seize upon every instance of conflict and turn them into racially motivated incidents. The so-called racial incidents of Ferguson and Staten Island had more to do with lack of respect for authority and how we administer justice than it did with the color of one’s skin.

We have seen devious wannabes take advantage of these tragic events and turn them into self-serving cause celebres. Where are the politicians who are asking the right questions? Where are the leaders who would bring us together rather than divide us?

The murders of the police officers on a Brooklyn street are the logical conclusion to those who would fan the flames of anarchy and those who fail to fully support legitimate authority. Words create an atmosphere and those who utter them must take responsibility for the actions they cause.

Some have called for a moratorium on public demonstrations until after the funerals of the police officers. What nonsense! Where is the call to a complete end to this civil unrest that is the work of professional organizers and dissident groups who do not have the common good as their goal.As Catholics, we look to the ideals preached by Our Lord as the guiding principles that would guide us [note: here comes the cant, which has of course absolutely nothing to do with anything said earlier]. We seek love not hatred, unity not division, peace not warfare.

At Christmas, we should be celebrating a birth that changed the course of history and instead our attention is being captured by death and destruction.

The New Year gives us all a chance to start over. Let us imagine ways to recapture concern for one another. Let us rid ourselves of self-serving mouthpieces who profit from the evil of murder and mayhem.

Let Jesus free our minds of suspicion and let us rediscover a sense of mutual respect. Let us reject timeworn slogans that pull us apart. Let 2015 be the year when we all come together and truly care about each other.

Catholic diocesan thinking is, as a general rule, atrocious, so I acknowledge that this article may not be worth overthinking. But I will point out at least a few things. The first is simply its tone; it preaches respect, love, unity, etc. but the feeling throughout – until it suddenly veers into cant, which is the homiletic indicator of a coda – is disrespectful, hateful, and divisive. Far from “recapturing concern for one another,” this piece devalues other human beings: they are “rabble-rousers,” “phoney leaders,” “devious wannabes.” It’s a bit much to have the bishop’s newspaper complain about “self-serving mouthpieces,” but I suppose nothing rankles one self-serving mouthpiece as the attention given to another self-serving mouthpiece.

The second thing I will point out is that it really – really – is self-contradictory. Behind it – and behind all modern Catholic thinking – is the concept of the value and dignity of life. Really this is precisely the concept the protestors are upholding. In both the Ferguson and Garner cases, a human life was taken – and this did not, according to our legal system, even merit a trial. Two men died, and our justice system offers no recourse: the killers, who are known, walk free. I am not saying the killers were guilty before the law. But I am saying that our legal system is inadequate, and unjust, if it does not even deign to hold a public hearing concerning one man’s killing of another. And this was not one odd instance: it happened twice in a few short months, and has drawn attention to hundreds of other cases of potential police abuse of authority. The pro-life side of this argument is the one which claims that “black lives matter.” The only reform I want out of all this unrest is: everyone – even police – must be brought to account for the taking of human life. There may be cases of homicide where there will be no legal punishment, but the sanctity of life demands at least a trial.

And I will note that the public protests here in New York City occurred not when Garner was killed by a police officer. They occurred when the justice system refused to even hear the case. When there was no legal recourse, what good option was left for redress other than peaceable protest in the streets?

This brings me to my third observation. It is impressive to me how enduring in American life is the “silent majority” – the law-and-order people who liked Richard Nixon so much. It surprises me that people – and so many – really believe that the greatest danger of our time is “extreme lack of respect for authority.” These people think the legal system is just fine – which I think is implied in that phrase “lack of respect for authority and [lack of respect] for how we administer justice.” Our legal system does all they really require of it: 1) it is highly predictable 2) it follows wealth scrupulously. The “broken windows” theory of policing is more than a theory – it really is an American philosophy. If you don’t want to deal with the police, then you have a responsibility: your responsibility is to maintain appearances. The law will not bother you if you drive a tasteful new car, if you have a nice-looking, well-maintained home, keep all your paperwork in line (best if you hire a professional for such things), dress nicely and expensively, and have good manners and know when to shut up and just wait for your lawyer to show. For a lot of people this is the highest form of justice: they even get angry that some people are not satisfied with it. How much simpler can it get? Why can’t these black people just get it?

It is striking to me how thoroughly the Catholic hierarchy belongs to this “silent majority.” That they would have been Pharisees back in the day, and executed Jesus in a heartbeat, is obvious. The Law might have been unjust, and might have promoted hypocrisy, pettiness, and cruelty, but it was clear and obvious and predictable. What more could long-haired Jesus – from Nazareth, not a respectable neighborhood – have wanted? He got what he deserved, in the end. The Catholic Church, despite an odd glimmer of awareness from the current pope, remains what it has been since the days of Constantine: a man standing immobile in the night, wearing a headlamp which faces behind him. It illumines the way for the people walking away from it.

I would like to call attention to one last paragraph:

Race is a factor but it is not THE factor. Our country has faced up to its racial divide and has been making great strides in bringing all peoples together. For the most part, people of good will live and work side by side, regardless of race, color, or beliefs.

This is the kind of thing that white people believe until they, say, marry a black person, or adopt a black child. Then all of a sudden they see. It is mere wishful thinking. Where I live – in a blue state – white people call Martin Luther King Day “Nigger Day.” Teenage boys make fun of the fact that I have no problem with black people: “God John, are you fucking blind? I hate niggers. I fucking hate them.” Throughout large parts of this country, white people think that the country would be better off if all black people vanished the next day.

It is true that there is some evidence that the police will treat you badly if you are poor, even if you are poor and white. But since so many blacks are poor, and they are often poor because employers pass them over in favor of candidates of other races, this is splitting hairs. Any person who has walked this land cannot help but feel the immense wrong which has been done to black people, a wrong which has persisted for generations and shows no sign of stopping. And anyone who knows history knows the depth and perversity of this injustice – I just recently read Chris Rock talking about his mother having to go to a veterinarian in South Carolina to get a tooth pulled, and having to come to the back door, and slyly, because the white people in town would refuse to patronize the vet if they knew he used his instruments on black people. Things are better, fine; now a black can sue a dentist if he refuses to treat him; but let’s not pretend that “our country has faced up to its racial divide.” The slogan “Black lives matter” has impact because it’s so obvious that for the most part, in this country, black lives don’t matter. Not as much as other lives. Not even to bishops in churches which purport to follow Christ. Is it really too much to ask of them that they support a public trial for people who kill other human beings?

Cherry Birch.

29-Dec-14 Speaking of “you are what you stack,” I was doing my usual winter work of splitting wood and I couldn’t help but admire this stick of cherry birch, Betula lenta. This birch was known as “mahogany birch” for its beauty as a furniture wood, which you can see in this picture (look at the lovely red-toned heartwood). It takes a stain very nicely too, and was used widely as a veneer wood. The maroon inner bark, clearly visible in this picture, doesn’t show up in furniture much but it sure is pretty to look at, on a winter’s day. The wood is even more desirable for furniture because it is rotten firewood, exceptionally stringy and difficult to split and not much of a burner either. It doesn’t show up in my stove much – this piece came from a neighbor.

Speaking of “you are what you stack,” I was doing my usual winter work of splitting wood and I couldn’t help but admire this stick of cherry birch, Betula lenta. This birch was known as “mahogany birch” for its beauty as a furniture wood, which you can see in this picture (look at the lovely red-toned heartwood). It takes a stain very nicely too, and was used widely as a veneer wood. The maroon inner bark, clearly visible in this picture, doesn’t show up in furniture much but it sure is pretty to look at, on a winter’s day. The wood is even more desirable for furniture because it is rotten firewood, exceptionally stringy and difficult to split and not much of a burner either. It doesn’t show up in my stove much – this piece came from a neighbor.

This morning I was starting my fire with bits of newspaper, and it so happened that a copy of The New York Times from some months ago contributed to these pyrogenics. No headlines are quite so interesting as old headlines – I sometimes find that it takes me a few extra minutes to get the fire started just because something catches my eye from my paper-stack. But what I found made me alternate between disgust and wonder, that there could be a society somewhere, far away from Wildcat Mountain, of such moral decrepitude and intellectual vapidity that it had news articles like these (and this was just on ONE PAGE of this newspaper):

One article was called “You Are What You Stack,” about buying coffee table books. “In the aspirational space known as the living room,” this article preached at me, “coffee table books tell the world what kind of person you want to be.” (Now if only I had a coffee table. (Or a living room.))

Another was called “If A Picasso Had Buttons.” The article was about the growing industry storing clothing for the uber-rich. Their clothing gets treated very well, apparently, cleaned with all kinds of chemicals (which also can show the world what kind of person you want to be, apparently – organic, heavy-duty, gluten-free, whatever), individually wrapped and placed in expensive storage buildings with advanced climate-control systems. “Like treasured works of art, the clothing of the rich is not just stored but pampered.” I was actually kind of glad this article was run, just because it confirmed me in my plan to write a letter to Pope Francis asking him to reopen the cases for canonizing Robespierre and Madame DeFarge. I mean really, talk about fattening yourselves for the day of slaughter.

Then there was “Roll Over? Fat Chance.” It was about gyms and special diets for dogs. “More than half the dogs in America are overweight, giving rise to new diet and exercise programs.”

I had to write these words down, they were such a satire, before crumpling up this single sheet of paper and putting it in the stove. What is alive today, tomorrow is cast into the furnace.

On the Feast of Stephen.

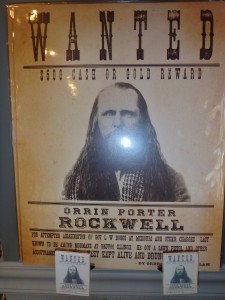

27-Dec-14 My bike trip this past spring brought me through Nauvoo, Illinois, a Mormon town. It is a tourist town, and a pleasant place, with the prosperity and wholesomeness once thought proper to all rural America but now almost the exclusive property of the Mormons. The lawns are crisply mowed, families walk blithely down the streets together, and the restaurants serve fresh apple pie. There are tourist shops selling Mormon-themed Christmas tree ornaments, pillows, and wall hangings. But one of the items in one of the shops caught my eye because it seemed so out of place among all this niceness: a bronze bust of a long-haired, long-bearded man whose visage was glazed by a smug, pusillanimous vacancy most unusual among the kind of heroes who are memorialized in bust-form. The name “Porter” was scrawled on the base of the image. I didn’t know who he was. Not far away was a large reproduction of a “wanted” poster, with a photograph of this same man which looked positively frightening – the hollow eyes of a conscienceless, stupid, vengeful, religious bigot. His name here was given as Orrin Porter Rockwell. The same poster was reproduced as a refrigerator magnet also.

My bike trip this past spring brought me through Nauvoo, Illinois, a Mormon town. It is a tourist town, and a pleasant place, with the prosperity and wholesomeness once thought proper to all rural America but now almost the exclusive property of the Mormons. The lawns are crisply mowed, families walk blithely down the streets together, and the restaurants serve fresh apple pie. There are tourist shops selling Mormon-themed Christmas tree ornaments, pillows, and wall hangings. But one of the items in one of the shops caught my eye because it seemed so out of place among all this niceness: a bronze bust of a long-haired, long-bearded man whose visage was glazed by a smug, pusillanimous vacancy most unusual among the kind of heroes who are memorialized in bust-form. The name “Porter” was scrawled on the base of the image. I didn’t know who he was. Not far away was a large reproduction of a “wanted” poster, with a photograph of this same man which looked positively frightening – the hollow eyes of a conscienceless, stupid, vengeful, religious bigot. His name here was given as Orrin Porter Rockwell. The same poster was reproduced as a refrigerator magnet also.

This man was known as “the destroying angel of Mormondom,” the marshall and Officer of the Peace in Salt Lake City under Brigham Young. He had been accused of shooting Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs – the governor who had driven the Mormons out of Missouri – but the grand jury failed to indict him, due to lack of evidence. Rockwell never quite denied the charge – all he did was cryptically aver that he had “done nothing criminal.” Fitz Hugh Ludlow, a New York writer who was travelling through the West with Albert Bierstadt when he met Rockwell, said of him, “He was that most terrible instrument that can be handled by fanaticism: a powerful physical nature welded to a mind of very narrow perceptions, intense convictions, and changeless tenacity. In his build he was a gladiator; in his humor a Yankee lumberman; in his memory a Bourbon [the old term for an extremely conservative Southerner]; in his vengeance an Indian. A strange mixture, only to be found on the American Continent.” Ludlow’s characterization after meeting the man in person was especially striking to me, because I had felt similarly just by looking at a photo of him. Rockwell had the reputation of being Young’s personal assassin; Rockwell merely said of his career that he “never killed anybody who didn’t need killing.” Mormon President Joseph F. Smith made it clear that while he might have been a murderer, he was a Mormon murderer, who was loyal to the tribe, and that was all that really mattered: “They say he was a murderer; if he was he was the friend of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, and he was faithful to them, and to his covenants, and he has gone to Heaven and apostates can go to Hell.”

This man was known as “the destroying angel of Mormondom,” the marshall and Officer of the Peace in Salt Lake City under Brigham Young. He had been accused of shooting Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs – the governor who had driven the Mormons out of Missouri – but the grand jury failed to indict him, due to lack of evidence. Rockwell never quite denied the charge – all he did was cryptically aver that he had “done nothing criminal.” Fitz Hugh Ludlow, a New York writer who was travelling through the West with Albert Bierstadt when he met Rockwell, said of him, “He was that most terrible instrument that can be handled by fanaticism: a powerful physical nature welded to a mind of very narrow perceptions, intense convictions, and changeless tenacity. In his build he was a gladiator; in his humor a Yankee lumberman; in his memory a Bourbon [the old term for an extremely conservative Southerner]; in his vengeance an Indian. A strange mixture, only to be found on the American Continent.” Ludlow’s characterization after meeting the man in person was especially striking to me, because I had felt similarly just by looking at a photo of him. Rockwell had the reputation of being Young’s personal assassin; Rockwell merely said of his career that he “never killed anybody who didn’t need killing.” Mormon President Joseph F. Smith made it clear that while he might have been a murderer, he was a Mormon murderer, who was loyal to the tribe, and that was all that really mattered: “They say he was a murderer; if he was he was the friend of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, and he was faithful to them, and to his covenants, and he has gone to Heaven and apostates can go to Hell.”

I was looking over my pictures from the bike trip all when I saw the pictures of Rockwell memorabilia all I could think of is how depressing all this revenge is, all this killing, all this partiality, all this endless retaliation, all this bad news. How depressing it was that some human being had decided to make a bust of Rockwell, and it had been popular enough to be turned into a tourist knick-knack. And of course we all know the current news: the police killings of black men, and black men’s killing of police. And we know how the retaliatory killings have changed the conversation, how now it all probably will add up to stagnation, and stagnation in a kind of hatred.

And yet in church there was no Orrin Porter Rockwell in the Gospel story, no bust to pick up at the cathedral gift shop of Jesus’s “destroying angel,” who dealt with anyone that Jesus determined “needed killing.” None of the apostles is celebrated as the one who took down Pilate after the fact, or settled the score with Caiaphas, or tracked down the man who nailed Jesus to the cross. The Gospels don’t even record what happened to these men – there is no joy that they later died choking on a tart or the like. Judas of course hanged himself, but even this feels like a tragedy, no triumph. Peter wished that he could be Rockwell – he pulled out his sword for Christ – and he was stopped by Jesus. Some Christians have claimed that that period of time – when Christians were supposed to bring Good News rather than just more bad news – ended when Jesus died, which is, of course, why St. Stephen, who seems to have died by Christian principles as much as he lived by them, is so important. Vengeance and retaliation was not the point. One person is named among the killers of St. Stephen, but he is not treated badly by the church. In fact, he went on to become the most celebrated apostle of them all – St. Paul. For a brief while at least, there was a group of people who were articulating an entirely different way. It is, for me, a little glimmer of hope. Now of course the question is how to convince the “Christians” in America and elsewhere of this.

The poetic justice of placing St. Stephen’s feast day next to that of Christ himself is easily felt. It might have been easy – indeed, it is, right now, easy – for Christians to say that Christ’s nonviolence was proper for him, but not meant for all of us normal mortals. St. Stephen followed in his footsteps, and established that Christ was not supposed to be merely a distant object of nominal worship, but an exemplar as well.

Stephen is also considered by scholars to be one of the figures who recognized just how truly revolutionary Jesus was, and insisted on a break with temple Judaism and the Law. Acts records that Stephen came to prominence as one of the “Hellenistai” – the Greekists, a term whose precise meaning is disputed – who protested that the early Christian community, in their work taking care of poor widows, cared only for “Hebraiai” (presumably Hebrew or Aramaic speakers, as opposed to Greeks). Stephen seems to have objected more thoroughly to the Jews-first approach, and apparently advocated a break from the Law and the Temple. “That man,” Acts reports, “does not stop speaking against the holy place, and the law; we have heard him say that this Jesus of Nazareth will destroy the temple, and change the traditions which Moses has given us” (6:13). The Catholic commentary in the New American Bible on this verse is: “The charges that Stephen depreciated the importance of the temple and the Mosaic law and elevated Jesus to a stature above Moses were in fact true [I love how Biblical commentators, at a distance of two thousand years, can weigh in with such certitude on these matters]. Before the Sanhedrin, no defense against them was possible.” And in the speech of Stephen reported in Acts he really does not defend himself against these charges. He embarks on a lengthy disquisition on the history of Judaism, which makes it clear that it existed long before the Law and long before the Temple, which were hence not determinative: what was important was the relationship of promise which had begun with Abraham. “The most high,” he concludes, “does not dwell in things made by hands [Latin “Non Excelsus in manufactis habitat” – which should be put onto every church and monstrance in the world]… The Lord says, ‘What house will you build for me? What is my “place of rest”? Has not my hand made all these things?’” That this was blasphemy against God’s house was quickly determined:

Casting him out of the city they began to stone him; the people at the stoning, taking off their himations [the Greek toga], laid them at the feet of a young man who was named Saul. And they threw their rocks at Stephen, as he called upon God and said, “Lord Jesus, take my spirit.” Then falling to his knees, he shouted in a great voice, saying, “Lord, do not hold this sin against them.” And when he had said this, he fell asleep. And Saul was there, approving of his execution. (7:58-8:1)

This is the prototypical martyr story, and Stephen is called in the Greek church the “protomartyr.” The details are nevertheless interesting: the eventual Christian overthrow of the practice of stoning, despite the fact that it is “Biblical”; the conviction that death is not the end but a “falling asleep”; the shouting of his last words, almost as an expression of strength, as opposed to mumbling them; the way that they convey that what is happening is wrong but not determinative – there is still some hope for the killers to break free of this cycle; the effect such a scene must have produced on the spectators, including in this instance the future Paul.

But it shows no sign of what I will call a “martyr complex.” Nietzsche believed that the Christian phenomenon of martyrdom was pure ressentiment, resentment disguised as obedient suffering: that it was “a triumph of Judaism,” a glorification of a sick, debilitated, bookish weakness. He believed that Christians went to their suffering the way a child hopes to die: “I’m going to die, and then you’ll all be sorry!” All human history before the prophets of Judaism, he thought, had glorified the victor: but now there was a kind of race to the bottom, as the Judeo-Christian “transvaluation of values” taught mankind to strive for the attention and sympathy that comes from being a victim.

Nietzsche is certainly describing something when he describes this martyr complex, but I don’t think he is describing the death of Stephen, or Christ, or Jerome of Prague, or Wyclif, or Martin Luther King, or any of the other true Christian martyrs. Stephen’s words – “do not hold this sin against them” – are quite the opposite of the martyr complex, whose entire point is to have something to hold against someone.

This does not necessarily mean that Stephen could not be lying, and actually meaning to damn his opponents to hell by being so goody-goody with them. I know full well that this kind of thing exists; but there is no particular evidence of it here, and I know also that its opposite exists as well. There is a way of being which allows us to suffer injustice without truly being its victim – and what I mean by that is, without losing our integrity. And fundamentally, it is our integrity which is the question. And this way of being, which Jesus and Stephen practiced, and Gandhi called ahimsa, is absolutely necessary to achieve transformation in civil societies.

I have thought a great deal about this problem, as it is one of the central problems of our moral existence – how to respond to injustice, when accommodation and overt resistance both seem to produce deplorable results. We are implicated in this problem constantly: when we see a child abusing a parent, or a parent abusing a child in a store; when we see children abusing each other in a classroom, or in our homes; when we see spouses abusing each other; or strangers in society; we feel that complaisance is no solution, but engagement does not seem to offer anything either. On a political scale the problem seems to be even worse. We supposedly use our military as a tool of moral correction, but we very rarely use it well. A friend of mine who fought in Iraq summed up the problem: “When I first started in Iraq I wondered how people could do bad things. By the time I finished I wondered how people could do any good at all.” Leaving the Iraqis to kill and torture each other seemed inconsistent with our own integrity, until we tried the alternative of getting involved, which was worse. We merely became the killers and torturers ourselves.

And I will repeat that I do not necessarily believe that isolationism is a solution. I think that any kind of spiritual transformation starts with what is near, and so we are always better off solving our own problems – in our nation, our states, our cities, our neighborhoods, our families, and our selves – but this does not mean that the proper response to every faraway problem is no response, or that we are all isolated in our own problems. And I do not necessarily believe that nonviolence is the only solution. I think it is exceptionally difficult to use violence well, but I acknowledge that sometimes it may be the necessary solution. Animals sometimes discipline their young with a swat, and I think we are still basically animals – not fallen angels, as the saying is, but risen apes. But how do we know when the “eye for an eye” approach is applicable, and when something else is necessary?

In fact I can say that I have, like most people, cherished memories of vengeance. And since I think I can make inferences from these stories – and because as primates we like stories like this – I will offer one. On a school trip in third grade – to the Museum of the American Indian – I was in a line of boys waiting to use a bathroom. The bathroom’s door-lock was not functioning. When it was my turn in the bathroom, one of the other boys threw the door open and kept it open, while all the other boys laughed at me being caught with my pants down in front of everyone else. I was quite powerless to close the door immediately, and I suffered immense mortification. Eventually I got to the door and shut it, and the teacher, hearing the commotion, intervened to keep order. All the way back to school on the bus I glowered through the window, watching the city pass by, and plotted revenge. The offending boy walked home from school every day; and he had to walk past my house. I did not have to do anything while in school; I would have opportunity later. At the end of the day we all had to line up at the front of the room with our coats and backpacks on. I finished my classwork and packing before everyone else, and was the first on line. Once the whole class was ready we walked down to the exit, and as soon as I was out the door I ran all the way home. I threw my backpack down, went back outside, checked to see if the offender could see me, and then, satisfied that he had not yet turned the corner of our block, I crouched behind a car and waited. After what seemed like an eternity he walked by. I sprang from behind him, grabbed his hair in my left hand, and proceeded to smash at his face with my right fist. I was a bit skinnier than he was, but wiry, and strong when motivated, and I had the element of surprise on my side. I yanked him around with my left hand so much I remember there being tufts of hair on the ground. I beat his face until it was slippery with his tears and my sense of revenge had been satisfied; and then I shoved him on his way and went home with an improved opinion of myself.

And I still don’t think that what I did then, as a child, was wrong, though I do believe that children can, in fact, do all kinds of things that are quite wrong. I can think of things which I did as a child which make me blush with shame to this day; but this is not one of them. I think many parents would today think that such behavior is wrong, and punish it; but my parents did not punish me. Why?

My answer to this question surprised me a little, once I had thought about it enough and come to my conclusion. Though I was different from the other kids and quite smart, I was not teased very much. I was different, but I was not a victim. And because of incidents like this, and others, the other kids knew this. It turns out that there are times when you fight, because you are not a victim; and there are other times when you do not fight, for precisely the same reason. It is not the fighting which is so important; it is the place it comes from. Sometimes bad things happen to us, but we are not victimized by it; our integrity, our humanity, is not impaired by the suffering. And we have a kind of instinctual sense of this: both I and my nemesis were satisfied with the results of the day. He did not give me further trouble – in fact we were friends again not long after – and I did not feel personally compromised by what I had done.

In part this was because my reaction was topical: I was not lashing out at him because my mother didn’t love me, or my father had left, or anything like that. That kind of spiritual robbing of Peter to pay Paul always leaves us unsatisfied, or, to persist in my terms, it does not take away the feeling of victimization. All you have done is add another person to the world’s total of victims. The result of this is just further self-loathing: and you feel even more a victim, now a victim of your own bewilderment, your lostness, your inability to solve your problems, your sense of guilt at having done this to someone else. I think we see this is many of the school shootings (and the most recent execution of the two New York City police officers), which do not seem to result in much satisfaction for the perpetrators. They always save their last bullet for the person they hate most of all: themselves.

It is quite possible to think of other circumstances where my actions actually would have made me ashamed, and where my parents might have punished me. One of them, in fact, might have been if the other boy had been himself acting out of some kind of displaced victimization. In that instance I might not have clearly seen it as a child, but my parents might have, and might have told me just to take whatever abuse he, in particular, gave me, because it would be wrong to beat up someone who was so troubled. And I suspect that our instincts – at least when reasonably well-trained and healthy – help us in such instances. Our consciences are troubled when we pick on the weak – on people who are already victims. We can sense that there is a displacement going on; sometimes we can only sense it after the fact, but we can feel that something is wrong. In that instance I think every good parent teaches forbearance and patience, and under this good tutelage we get more sensitive to what is happening in other people.

Indeed as we get older and the capacities of our compassion increase, we find it increasingly necessary to not fight; violence becomes less and less acceptable; we are less animal, and more human. That this is a form of strength, and not weakness, I think is almost always instinctually felt by people – that some people, even some people who do not fight back, even some people who suffer greatly, simply are not victims. They keep their integrity even under attack from other people: the attack says much more about the weakness of the attacker than it does about the weakness of the attacked.

Again, I do not deny that there are people who are compliant in injustice because they have, in fact, been robbed of their integrity: this certainly occurs. I remember seeing a young child slap his mother in the face, and she did nothing about it, because she no longer knew what to do. She was no Stephen speaking truth to power; she was simply weak and being trampled on. She was no martyr, or witness to the truth; at best she was working on her martyr complex – maybe she would be able to control her son later that way. There are also parents – and adults – who act violently for precisely the same reason that she did nothing: because they do not know anymore what else to do. They too are weak and trampled on, and we can expect nothing good of violence of this sort. Both are responses of victims, of people who feel temporarily unable to live their own lives, who feel powerless, and whose dignity has been lost.

One of the things I feel quite sure of is that we must distrust ourselves whenever we feel ourselves in this state. It seems to be almost impossible to see anything accurately when we feel powerless; and the result is some kind of displaced, inappropriate response. And, quite terrible to say, there is a tremendous cultural pressure to groom one’s own victim status: I don’t quite understand why. There is a kind of cultural cache to being a victim, and people will compete for the honor. (It is generally tied to group-identities as well, also a very dangerous, unstable emotional area: from the religious perspective, the only acceptable tribe is that of all creation, and all other thinking from any other premise is bound to be faulty.) Nietzsche I think blamed Christianity for this, but he was wrong: Achilles himself sat and sulked like a baby because his “prize” – his sex-slave – was taken away from him. He wanted to see as many Greeks as possible killed while he was gone, so they would regret what they had done to him. In the absence of higher religious purpose and broader perspective, this egocentric thinking seems to take over everything. Journalism, and tabloid and internet journalism in particular, plays to this aspect of ourselves obsessively. Bad religion plays the same game. To get Republicans to believe that they are the victims of Democrats (and vice versa), whites of blacks (and vice versa), women of men (and vice versa), Christians of Muslims (and vice versa), the poor of the rich (and vice versa), is the constant work of news outlets. That injustices are committed is obvious. But I am certain that we must – must – be cautious whenever we feel even the slightest feelings of victimization and anger. One of the things that is most striking about people who do bad things is how consistently – almost universally – they feel they are the real victims. A person who believes he is a victim is capable of almost anything. The result is to create more victims, and make injustice flourish. Even to express the feelings of victimization and outrage seems to have a negative effect on other people.

But how to suffer without being turned into a victim is a most difficult spiritual problem. One thing is certain – we will all, certainly, suffer at each other’s hands. But some people – the ones to whom praise will come – will manage to transform their suffering into something else, rather than transmit it to someone else. But every form of pain which is not transformed will, in the end, be transmitted. We see it with parents and children; teachers and students; and society as a whole. The feast of Stephen commemorates one man who by not returning evil for evil, managed to take a little bit of it out of the world.

[For more on Nauvoo and Mormonism, read another essay here.]

The Project.

19-Jan-15buy Gabapentin 300 mg uk

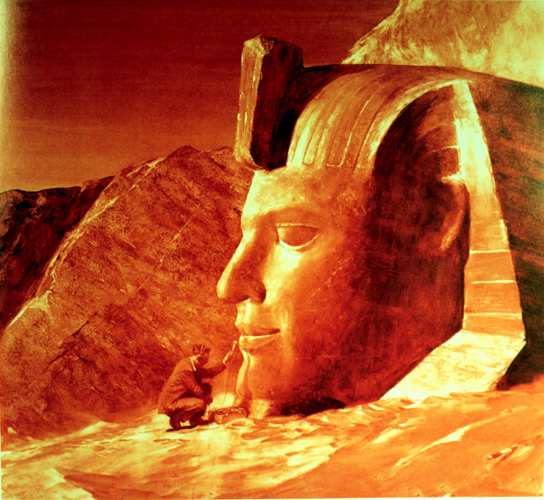

buy oral Pregabalin I find this image, of a man putting a microphone and recorder to the lips of the Sphinx, so compelling an image for so much of what I find myself doing, and so much of what I think humanity as a whole has to do, to make sense of our new lives, which are somehow a continuation of the old, and far less free of them than we think. It is by Mark Tansey, and is called The Secret of the Sphinx.