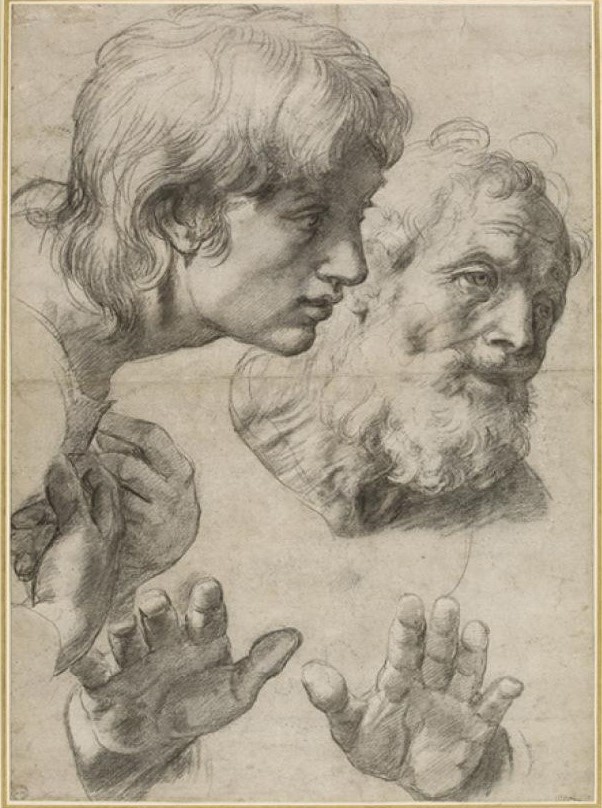

Today marks five hundred years since Raphael’s death; and a further tradition states that April 6th is the day of his birth as well. I’ve always loved School of Athens, and the Disputa, but really the piece by Raphael that moves me most is a preparatory sketch, one he executed for his final painting, the Transfiguration.

Today marks five hundred years since Raphael’s death; and a further tradition states that April 6th is the day of his birth as well. I’ve always loved School of Athens, and the Disputa, but really the piece by Raphael that moves me most is a preparatory sketch, one he executed for his final painting, the Transfiguration.

I saw this sketch at the Ashmolean Museum, while a student at Oxford. One of my (many) pleasures while there was to visit the print room at the Ashmolean; you request a folder – say, “sketches by Raphael” – put on gloves, and take your seat in the print room. A curator brings the folder out, and sets it on a stand in front of your seat, leaving you to the pleasure of going through the folder admiring the sketches. The curator lurks, to make sure all is well, but there is a lingering sense in the place that all those who request a folder of Raphael sketches are gentlemen, and to be trusted with such things.

I enthused about this print to my mother, and when she came to visit me at Oxford she made a trip to the museum and saw it for herself (I had something or other to do – write a paper or something like that). From that trip she brought me a print of the sketch, which traveled with me from place to place for years. I may well have it here at the house, but I’m sure if I have it it has suffered over the years: it was tacked up at first in my room at Oxford, then it traveled to the United States, graced my room at Princeton, then wandered to New York City. It never got framed, and acquired some dirt and creases and became unpresentable eventually.

But I never tired of looking at it. Now it makes me think of my mother; I think she saw, in Raphael’s old and young apostles, something like herself and her son. I was so forward, so intense in my interests, so curious, as the young St. John in the sketch; but also held back somehow; I desperately wanted to, but did not put my hands to the things I desired. Whereas old James sees something else; he does not thrust himself into the action, but merely watches with feeling; his curiosity has been satisfied already, he knows what he is seeing, and the track of a tear is visible on his face. His hands spread slightly though, as if he has to calm himself and keep himself in.

In the painting, these two figures are not to my eye especially remarkable, so much less feeling is in the painting, than in the sketch. I think this is generally true of Raphael: I find myself often unmoved by his paintings, but his sketches, his lines, seem to have a depth beyond all other artists.

And that sketch for me is not only great art, but deeply personal. I am thankful for this – thankful that she had such a relationship with great art, and thankful that she shared it with me. It feels like something deep and lasting, something that means something to me twenty years later, and will still mean something in twenty years more, and even be to some extent communicable and shareable with others. Fine, beautiful things are like this: they take our love and interest and hold them, like heat held in a stone, such that others can feel them long afterward. Someday perhaps my own children will discover Raphael the draftsman, and I will be the one with the tear in my eye, hands slightly outstretched, while they peer with curious beauty at the life of the world.

Shakespeare, In Praise of More Babies.

10-Mar-20When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night;

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls all silver’d o’er with white;

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd,

And summer’s green all girded up in sheaves,

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard,

Then of thy beauty do I question make,

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake

And die as fast as they see others grow;

And nothing ’gainst Time’s scythe can make defence

Save breed, to brave him when he takes thee hence.

—

“Breed” here seems to function as a noun – “offspring,” or infinitive, “to breed, to make babies.” And “him” I suppose is death more than God. Or of course “breed” could just be the Venereal deed, as that only by its full fructification seems to stand against Time’s scythe. The world as I have known it is running down; the youthful faces I knew are lined and careworn, and are not as I knew them. But my children are still this day’s creation, and the world is all new to them.